Can dogs have psychosis

Dogs can have a type of bipolar issue and other mental illnesses that affect their quality of life, especially if they go undiagnosed and untreated. It is not just bipolar disorder than can affect your pup, but any mental illnesses ranging from depression to anxiety to PTSD to obsessive-compulsive disorder. These mental disorders do not consistently present as they would in humans but have been diagnosed and visible in some aspect in many dogs. These illnesses tend to show up more often when a dog has been mistreated or in captivity. The chemicals in the brain can instigate a mental illness when a dog is treated poorly and unable to cope. While mental illness in a pet is troubling, most issues are treatable if diagnosed. Dogs, as with humans, can undoubtedly live full and happy lives if mental health is cared for properly.

Bipolar Disorder

While dogs can certainly be prone to mental illness, bipolar disorder is one that needs to be clarified. We can not just transfer the human experience to our dogs. Untreated bipolar disorder in people means there are manic mood swings and emotional instability. There are swings from the highs of mania and lows of severe depression. Dogs do not have this ability to swing to emotional extremes. That is not to say they cant change moods; they can certainly have a switch from a good mood to a fearful one or to one of depression. However, dog brains do not function in the same way as humans, meaning that a bipolar disorder will not present the same. Their lack of language and difference in cognitive processes means they may have mood swings but not in the same way bipolar individuals do.

This mental disorder can be treated with behavior therapy but also SSRI medication in extreme cases. Fluoxetineis the generic doggy Prozac and can be used to battle the manic swings your pup may be having.

Depression

Although bipolar disorder is dissimilar in dogs when compared to humans, depression is quite evident and runs along the same path for dogs as people. We obviously cant know what a pup is actually thinking, but surrender to shelter, the death of a companion can createa change in your dog'sbehavior and show the symptoms of depression. They may not eat, or they may pace or be unsettled. They may be subdued and uninterested in the things around them. Their emotions, in this case, are very similar to humans when it comes to depression.

Treatment for depression is similar to that in humans. Exercise, good food, and a supportive family. Get your pup outside for a walk or to play. A good game of fetch with a tennis ballor a run at the dog park will help. If meds are needed, then something like Fluoxetine may be prescribed. Either way, getting an early hold of it is vital, so your pup can go back to their happy ways.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Dogs are now seen to be exhibiting PTSD as their human counterparts do. It has been found in dogs returning from the military in the Middle East who show the same behaviors as the humans that have returned as well. Unfortunately, dogs are often not treated for this mental disorder properly and are euthanized rather than given support. Luckily, veterinarians are starting to diagnose the disease accurately and offer suitable training methods to help canines recover from the emotional trauma they have endured.

While medications can be used to treat PTSD, there are other ways suggested as well. Systemic desensitization may be helpful. Exposing a dog to whatever its trigger is, such as noises, and offering Treatshelps begin the desensitization. They hear the noise quietly and then as it gets louder, they are given treats while staying calm. They start to associate the sound with treats, not trauma.

Anxiety

A prominent mental illness in dogs is anxiety that manifests itself when separation happens. A dog can become extremely anxious when you leave them at home while you go out. Part of this issue stems from their inability to understand if you will ever come back. They don't know your intentions and begin to panic. In their state of fear, they can do damage to the things around them. They can damage household and personal belongings as well as have accidents even though they are house trained. Anxiety can be treated and worked through proper training and attention. Sometimes meds are used in extreme cases.

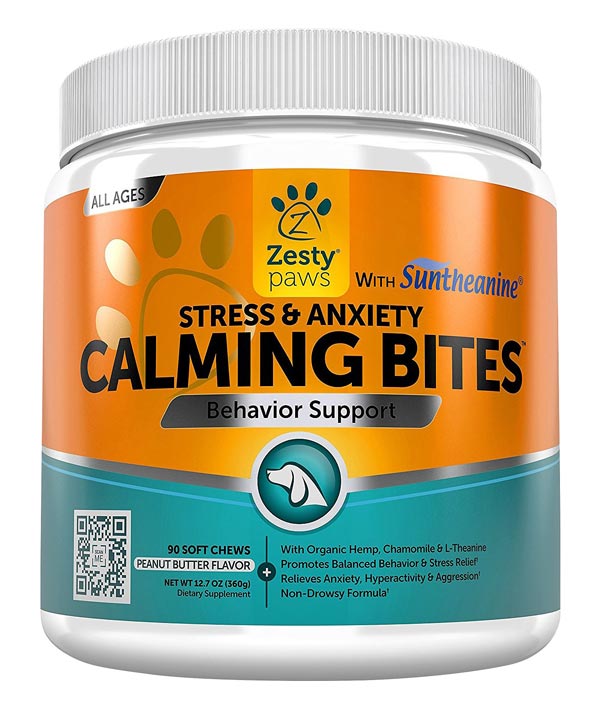

As with other mental disorders, anxiety can be treated with medication. However, it is best to try other methods and leave the meds as a last resort. Along with exercise, there are supplementsto help do this. By offering these to your pet every day, you can reduce stress and anxiety, causing their anxiety issues.

Social Anxiety

Dogs are social beings and pack animals. While some can be standoffish, they still all require the attention of love in some manner. Dogs that were raised in social isolation can exhibit anti-social behavior. If they were raised alone as puppies and never socialized with other dogs or people, can become very anxious if put in a situation that is new to them. They react negatively, not because they do not want to socialize but because they dont know how to. They can become aggressive as they can not read the social cues on how to interact appropriately. The situation becomes emotionally charged for them. They require love and slow social interaction if there attempts to overcome this.

Final Thoughts

Dogs can struggle as humans do with mental health issues. Although bipolar disorder and other mental health problems may not present the same as in humans, they do exist in the canine world. It's important to acknowledge this and seek treatment for our pets as necessary. Not only is physical well being important for your dog, but their mental health welfare is as well. We are responsible as owners to mindful of both and seek help for our pets when they are struggling with the mental illness issues that can affect their quality of life.

Why Don't Animals Get Schizophrenia (and How Come We Do)?

Why Don't Animals Get Schizophrenia (and How Come We Do)?

Research suggests an evolutionary link between the disorder and what makes us human

By Bret Stetka

Many of us have known a dog on Prozac. We've also witnessed the eye rolls that come with canine psychiatry. Doting pet ownersmyself includedascribe all sorts of questionable psychological ills to our pawed companions. But the science does suggest that numerous non-human species suffer from psychiatric symptoms. Birds obsess; horses on occasion get pathologically compulsive; dolphins and whalesespecially those in captivityself-mutilate. And that thing when your dog woefully watches you pull out of the driveway from the windowthat might be DSM-certified separation anxiety. "Every animal with a mind has the capacity to lose hold of it from time to time" wrote science historian and author Dr. Laurel Braitman in "Animal Madness."

But theres at least one mental malady that, while common in humans, seems to have spared all other animals: schizophrenia. Though psychotic animals may exist, psychosis has never been observed outside of our own species; whereas depression, OCD, and anxiety traits have been reported in many non-human species. This begs the question of why such a potentially devastating, often lethal diseasewhich we now know is heavily genetic, thanks tosome genomically homogenous Icelanders and plenty of other recent researchis still hanging around when it would seem that genes predisposing to psychosis would have been strongly selected against. A new study provides clues into how the potential for schizophrenia may have arisen in the human brain and, in doing so, suggests possible treatment targets. It turns out psychosis may be an unfortunate cost of our big brainsof higher, complex cognition.

The study, led by Mount Sinai researcher Dr. Joel Dudley, proposed that since schizophrenia is relatively prevalent in humans despite being so detrimentalthe condition affects over 1% of adultsthat it perhaps has a complex evolutionary backstory that would explain its persistence and exclusivity to humans. Specifically they were curious about segments of our genome called human accelerated regions, or HARs. HARs are short stretches of DNA that while conserved in other species, underwent rapid evolution in humans following our split with chimpanzees, presumably since they provided some benefit specific to our species. Rather than encoding for proteins themselves, HARs often help regulate neighboring genes. Since both schizophrenia and HARs appear to be for the most part human-specific, the researchers wondered if there might be a connection between the two.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To find out, Dudley and colleagues used data culled from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, a massive study identifying genetic variants associated with schizophrenia. They first assessed whether schizophrenia-related genes sit close to HARs along the human genomecloser than would be expected by chance. It turns out they do, suggesting that HARs play a role in regulating genes contributing to schizophrenia. Furthermore, HAR-associated schizophrenia genes were found to be under stronger evolutionary selective pressure compared with other schizophrenia genes, implying that the human variants of these genes are beneficial to us in some way despite harboring schizophrenia risk.

To help understand what these benefits might be, Dudleys group then turned to gene expression profiles. Whereas gene sequencing provides an organisms genome sequence, gene expression profiling reveals where and when in the body certain genes are actually active. Dudley's group found that HAR-associated schizophrenia genes are found in regions of the genome that influence other genes expressed in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region just behind the forehead involved in higher order thinkingimpaired PFC function is thought to contribute to psychosis.

They also found that these culprit genes are involved in various essential human neurological functions within the PFC, including the synaptic transmission of the neurotransmitter GABA. GABA serves as an inhibitor or regulator of neuronal activity, in part by suppressing dopamine in certain parts of the brain, and its impaired transmission is thought to be involved in schizophrenia. If GABA malfunctions, dopamine runs wild, contributing to the hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thinking common to psychosis. In other words, the schizophrenic brain lacks restraint.

The ultimate goal of the study was to see if evolution may help provide additional insights into the genetic architecture of schizophrenia so we can better understand and diagnose the disease, says Dudley. Identifying which genes are most implicated in schizophrenia and how theyre expressed could lead to more effective therapies like, say, those influencing the function of GABA.

But the findings also offer a possible explanation for why schizophrenia arose in humans in the first place, and why it doesnt seem to occur in other animals. Its been suggested, Dudley explains, that the emergence of human speech and language bears a relationship with schizophrenia genetics, and incidentally also autism. Indeed, language dysfunction is a feature of schizophrenia, and GABA is critical to speech, language and many other aspects of higher-order cognition. The fact that our evolutionary analysis converged on GABA function in the prefrontal cortex seems to tell an evolutionary story connecting schizophrenia risk with intelligence.

Put another way, with complicated, highly social human thoughtand the complicated genetics at the root of higher cognitionperhaps theres just more that can go wrong: complex function begets complex malfunction.

Dudley is careful not to exaggerate the evolutionary implications of his work. It is important to note that our study was not specifically designed to evaluate an "evolutionary trade-off, he says, but our findings support the hypothesis that evolution of our advanced cognitive abilities may have come at a costa predisposition to schizophrenia. He also acknowledges that the new work didnt identify any smoking gun genes and that schizophrenia genetics is profoundly complex. Still, he feels that evolutionary genetic analysis can help identify the most relevant genes and pathologic mechanisms at play in schizophrenia, and possibly other mental illnesses that preferentially affect humans as wellspecifically neurodevelopmental disorders related to higher-cognition and GABA activity, including autism and ADHD.

In fact, a new study published in Molecular Psychiatry reports a link between gene variants associated with autism spectrum disorder and better cognitive function in people without the disorder. The findings may help explain why those with autism sometimes exhibit extraordinary skill at certain cognitive abilities. They also support Dudleys speculation that higher cognition might have come at a price. As we broke away from our primate cousins our genomesHARs especiallyhastily evolved, granting us an increasing cache of abilities that other species lack. In doing so, they may have left our brains prone to occasional complex dysfunctionbut also capable of biomedical research aimed at one day, hopefully, curing the ailing brain. As Dudley and others untangle the genetic underpinnings of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses in search of improved diagnosis and treatment, at least our pugs, poodles and pot-bellied pigs seem to be psychosis free.

Bret Stetka is an Editorial Director at Medscape (a subsidiary of WebMD) and a freelance health, science and food writer. He received his MD in 2005 from the University of Virginia and has written for WIRED, Slate and Popular Mechanics about brains, genomics and sometimes both. Follow Bret on Twitter @BretStetka.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science, or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about? Please send suggestions to Mind Matters editor Gareth Cook, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist at the Boston Globe. He can be reached at garethideas AT gmail.com or Twitter@garethideas.